This probably should bear a trigger warning for anyone personally effected by the Texas floods. It’s a little frightening, and is in no way meant to reopen wounds or pain from those who lost loved ones. It’s instead considering the fallout and subsequent negligence questions this tragedy has raised from a somewhat-disconnected perspective.

Like anyone with a soul, I was hit hard by the news of the Texas summer camp drownings this last summer. The scenes and tragedies were enormous, made the more painful by thoughts of my own children and how precious they are to me.

Understandably, the immediate devastation also saw a lot of people, angry and hurt, asking, “how could this happen?” And, now that the shock has started to fade a few months out, these questions have only grown into public and even legal controversy–particularly about the Christian summer camp, Camp Mystic, where the majority of the child deaths occurred.

To be clear, I have no special insight into the potential negligence of that particular camp nor the local authorities. I don’t even have much not-that-special insight, seeing as I’m a few States away and (thankfully) without relatives or friends directly effected. But the controversies, and “reckoning” brewing up on the internet, has gotten me thinking. For one, a sense of justice demands some answers to such a tragedy. But two (and more personally important), I spent several years in charge of safety for a similar Christian summer camp run by my wife.

That camp was much smaller than Camp Mystic, and in a completely different part of the country, but shared many of the same goals and challenges to safety any summer camp would hold. Part of the shock of Texas is it seems like it would have been so simple to avoid the tragedy. All that was needed was to heed the warnings and get out, and no one needed to perish. And so, the fact that really anyone died, or especially so many children, must imply some serious negligence on the authorities responsible for issuing warnings, the camp officials responsible for listening to the warnings, or both. But my even limited experience of my own summer camp gave me the feeling it wasn’t so simple.

Of course, leader’s decisions can help or hurt. People die because they’re sleeping and don’t get alarms, or alarms aren’t sent out, or installed in the first place, or rescue persons are delayed to be deployed, or weathermen make neglectfully wrong predictions. And again, I don’t know if there were some serious missteps with Camp Mystic or Texas leadership in particular.

But I do know there’s a long way between such culpably-bad choices and everyone emerging unscathed. Nature is powerful, and often even our best efforts are not strong enough to counter it. Especially with serious water events.

Let’s start with the warnings. Authorities can and do make predictions about severe weather. They can predict within some confidence that there will be rain, and can guess that it’ll be severe enough to pose threat of flooding. Beforehand, and even as flooding starts, they can warn that there will be floods. But the scary fact is that they can’t predict precisely how high and where the flooding will hit. They can only predict probability based on historic data of floodplains, mixed with their best-guess rain predictions.

This means the actual weather event often falls short of their dire warnings. Think of all the times the news called for rain all weekend, causing you to cancel your plans, only for it to drizzle for 3 minutes before staying warm and clear for the entire week. But it also means the weather event can outmatch their best predictions. And this is where things can easily go really wrong. To account for it, authorities could (and sometimes seem to) play on the side of caution with predictions, trying to build in some buffer on their warnings. But there’s an upper bound to this strategy, too. They can’t issue a code red 5-alarm fire drill every time the sky darkens. Society would shut down at every rainstorm, or else people would start to just ignore any warnings.

So the bottom line is weather forecasts/warnings can only get you so far. There is always a non-zero chance the observed weather will be far, far worse than can possibly be predicted or warned about. This is maybe most pronounced in flash floods, which by definition are quickly-developing, unpredictable weather events.

This opens up a lot of room for reasonable, well-meaning, and well-planned safety protocols to nevertheless fail incredibly short. Let’s say you’re in a hilly rural area in a large summer camp. You have structures and campers all over, close to the river and all the way up the many nearby hills. All your cabins are on high ground, at least 25 feet above the river. A severe storm with predicted flooding is rolling in fast, giving at most a few hours notice. How do you prepare for such severe weather?

Evacuation is extremely risky. You’re really in the middle of nowhere; there’s a lot of people to move, many very young; you have an adult-camper ratio designed for safety and efficiency at the site everyone’s presumed to be remaining for the entire week, not for a frantic wilderness march. It’s nighttime, pitch black, without cell service; roads are infrequent, all run through the lowlands. There’s significant safety risk in evacuating children through dark unfamiliar woods, without even considering the other serious costs to money/time/effects to the programming. Sheltering in place is infinitely preferable, with evacuation only as a last resort.

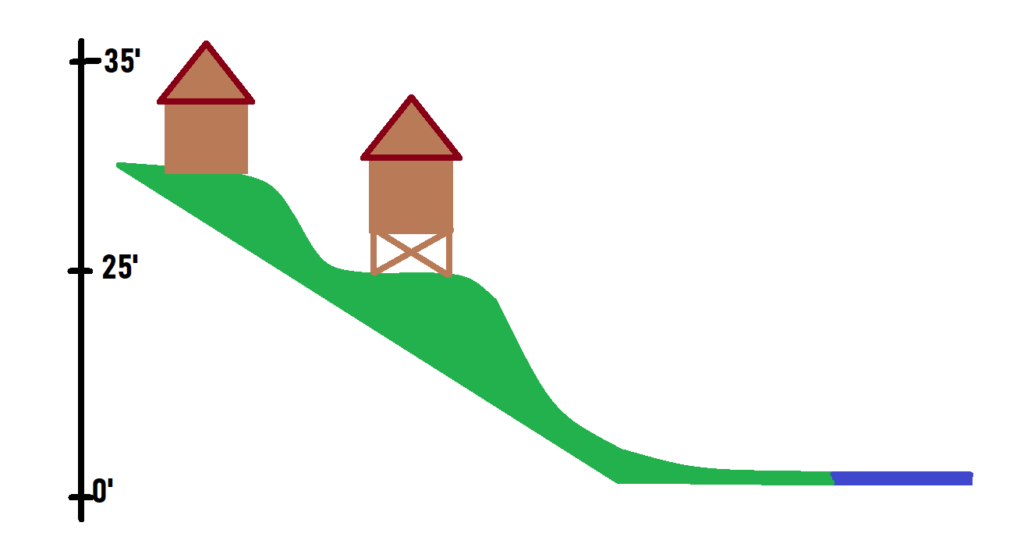

And, it seems shelter-in-place can be done. You move everyone to the cabins that are on the hill. Not everyone can fit in the highest cabin, but while some are 30-40 feet up, all of them are on stilts a good 10 feet above the water levels of flooding even on a bad year (excuse the poorly constructed visual):

But this isn’t even severe flooding. This is historic flooding. A fact which wasn’t (and couldn’t) be known ahead of time, by you nor the weathermen you’re relying on. That’s the first piece of what kills–severity.

The second piece is the “flash.” It moves fast. In fact, even if the weathermen could know it’s severity, they couldn’t warn you in time. The storm is forming so fast, and the water will reach so high, that you wouldn’t have time to get everyone into busses and through the lowland road network before the busses, and all in them, would be swept away by the deluge.

You nor they can reasonably know that, yet. But you take your job seriously, and so are paying attention nonetheless. You have lights and radios and weather maps. The waters rising, as you expect. 5 feet. 10 feet. 15 feet. And then…20 feet. 21 feet.

What to do? There hasn’t been time for authorities to predict the maximum water levels yet. It’s spiking faster than the meters can keep up. You realize after only a few minutes of careful observation that the water is going to keep rising, and the 25 foot cabins are threatened with the worst. You realize this isn’t a flood, but a big flood. So you realize the only option is to leave. On foot and into the woods if you have to.

But it’s already too late. Even to take the desperate option of running into the woods at the top of the hill. Only a few inches of fast water can kill. Less for children. And since the water moves so fast, by the time you had the possibility of realizing the direness of the situation, your exit is blocked. Your cabin is on stilts, and water is up to the doorway. Which means the ground you have to walk on to climb up to even higher ground is already under a foot of fast moving water. With trees and rocks and cars being carried away. You need rescue from boat or helicopter. You climb to the roof, hoping against hope that the water stops at 25 feet. But it goes to 26. 27. And doesn’t stop there. The entire building is knocked off its foundation, or the water starts flowing over the roof. And no one can hang on.

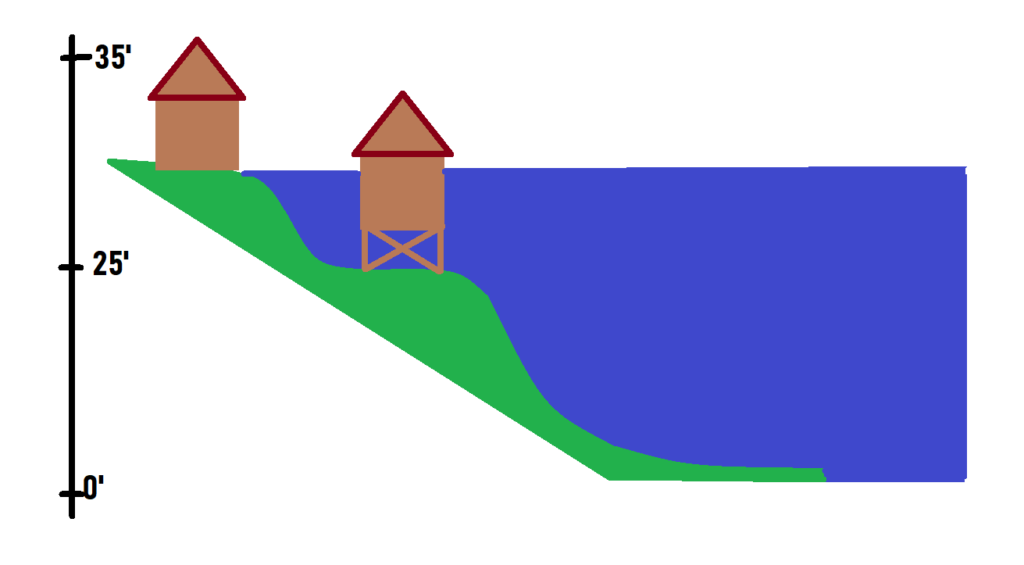

And so, without any “wrong” decisions being made by anyone, you have the fatal moment. One cabin has no escape, and the other does:

And notice that this is true even if the “lower” cabin is actually the same level as the topmost cabin. This is true even if the cabin closer to the river is higher than the cabin at the top of the hill, as seen here.

As the water levels continue to rise, the cabin farthest from the river still has an exit path. The one on stilts does not, even though it would appear to be the “safest” place to be on the campground during a flood situation. But then the swift water starts slamming trees and large rocks into the stilts, and before long the structure–and all inside–are lost forever.

Now you might say that this lack of an exist path is the problem, and means the safety strategy wasn’t very good. And yes, if you knew the water would reach that high, the entire safety plan to shelter in place in the first place wouldn’t have been very good, let alone the cabin placement. But as argued earlier, the impossibility (or even improbability) of knowing that means the safety plan is reasonable before the storm. Decisions have to be made for limited resources and multiple safety threats. In most cases, it’s not possible to account for the possible maxima of all these threats at once, let alone to do so with reasonable costs and staffing needs.

For example, if all you’re planning for is flood risk with infinite resources at your disposal, then build all cabins at the highest recorded water level plus 20 feet. But not only would that bankrupt you, but the terrain makes that impossible without seriously high stilts that then become a safety risk in a wind or lightning storm. Or, ensure there’s always an escape route for campers in their cabins for any water coming from the river. But, then the cabins may be hemmed in by the river if escape is needed from wildfires in the forest. Or, build cabins such and in such a location that there’s multiple quick and easy escape routes in case of an emergency. But, a way out is a way in, and that opens up liability for human dangers of creepers or thieves or other security risks.

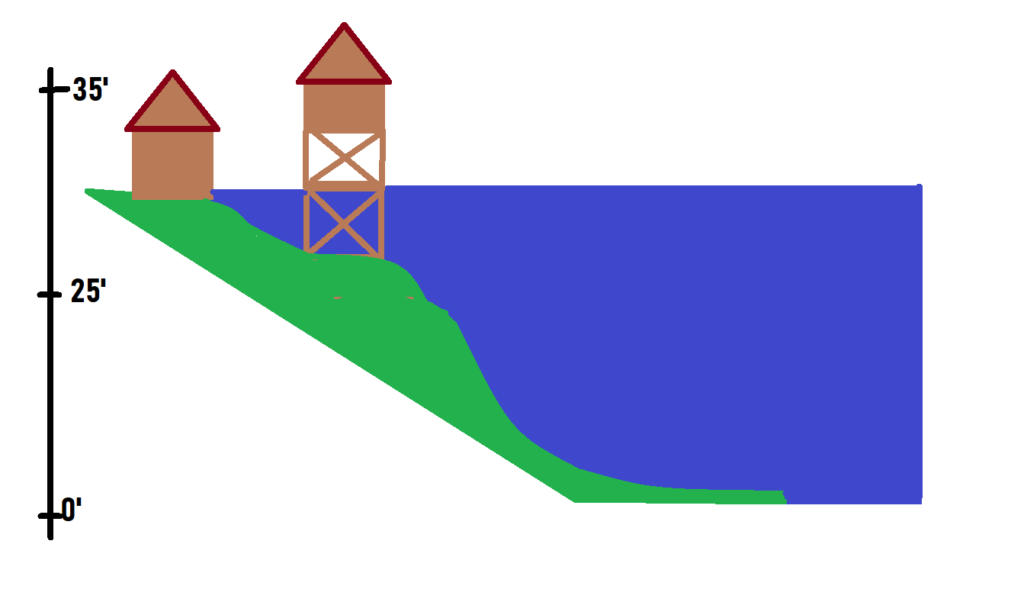

This (again) isn’t to say that this particular summer camp in Texas was victim to any of these limitations. Perhaps they had ample safer sites to build their cabins and did not do so. Maybe they had good indications that flooding was the primary threat to their cabins but still built them without a clear exit strategy. It’s just to say that it isn’t so simple as death = failed authority. You can have a perfectly reasonable safety plan with completely competent and dedicated staff, still overwhelmed by natures terrible power and swiftness. Sometimes it’s because a reasonable safety plan has to account for multiple contradictory threats, and so cannot account for the maxima of any single possible threat. Sometimes it’s just because the limitations of the geography you’re stuck with impose limits on safety planning, too. For example, consider this (last) poorly drawn figure:

If you have a site with only one modest hill, and water moves too quick and without enough warning to evacuate completely, that hill is your only option. But, even without stilts and a 360 degree path of exit around the structure itself, you’re still stuck–because that hill will quickly become an island in a serious flooding situation.

These factors are why flash flood kill people all over. Not just in “wilderness” facilities or situations, and not just in negligent locales. Summer camps have safety protocols so that when parents send their little boy or girl away, they can have confidence they will be just as safe at camp as they are under the parents’ own roof. The tragedy of fallen nature is that they’re not invincible even there. While the higher death count in Camp Mystic certainly bears investigating, people sadly perished from all over the area. When you’re caught in a drastic weather event–even in the place where you have all your resources, support network, communications, warning systems, and local infrastructure–you run risk of injury and death. Wildfires, floods, earthquakes, and storms prove this every season. Maybe some of those victims were passed out drunk in their basement with their phones off. But many did all they reasonably could to escape, and still met the ultimate price.

Let’s offer prayers for all the victims in Texas and everywhere. Let’s pray for justice if indeed there was any negligence in these cases. But let’s also be grateful for the normal safety that makes such cases so unusual and shocking, and respect the awesomeness of a nature that we cannot completely tame.